Florida Gael — A new page turner

A month ago, I was pleased to be interviewed by correspondent Brittany Ó Ruacháinn for the cover story on Florida Gael — a new publication focusing on all things Gaelic, and me being Florida-based author focused on Irish history.

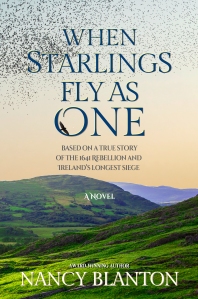

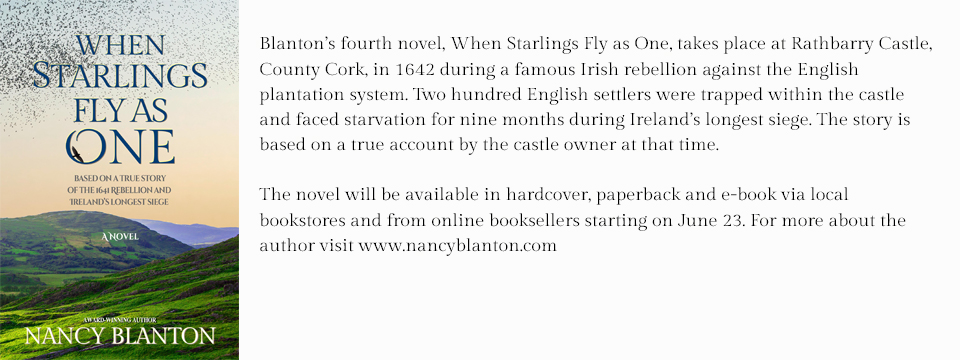

Brittany’s husband, Oisín Ó Ruacháinn, is founder and publisher of the monthly online newspaper which can include Welsh, Scottish and Irish groups, social clubs, sports, businesses, reviews, and more. It’s where you’ll find stories about Irish clubs making a difference in their communities, Scottish dancers offering an event, pub reviews from across Florida, and of course – books, like When Starlings Fly as One!

The first edition was published January 15, 2021, on Issuu, an online media platform that features magazines, newspapers, and portfolios, but now Florida Gael has its own website, and you can also find it on Facebook.

To learn more about this exciting new venture, Florida Gael, I’ve asked Oisin (pronounced oh-SHEEN) a few questions:

1. What inspired you to create Florida Gael? What urged you forward on the idea, and what was your first step?

As with many Americans, I have Irish ancestry; that ancestry inspired me to pursue Irish history. Being an historian, I often (before the pandemic) gave talks and lectures about Irish history to the general public, and was always inspired by just how popular the topic of Irish history, and certainly genealogy, was.

In the summer of 2020, I had just left a career as a journalist and moved into development. I had grown to thoroughly enjoy journalism, and I was looking to create a publication in my off-hours — of course, Irish affairs immediately sprang to my mind, so I decided to create Florida Gael: a publication not only for those people I had met as an historian giving talks on Irish history, but also for all those who descend from Gaeldom, i.e., Ireland, Scotland, and also Wales (not that I wouldn’t cover news from Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man!).

My first step into making Florida Gael a reality was to start feverishly networking, interviewing, and formulating a paper that I felt was interesting and pleasant to read — and I’ve been doing the same thing ever since.

2. What goals did you set for it? What do you hope to accomplish over the next few years?

To be quite honest, my initial goal for Florida Gael was just to have a small outlet for me to discuss Irish affairs in Florida — this quickly grew into something much more, and I’m delighted that it did. At first, my goal was just to have something out there, whether that be one article or a write-up on something interesting I found online. Today, I’m very proud to say that we have a full newspaper spread, and my future goals are more concrete: I intend, le cúnamh Dé, to eventually bring Florida Gael into press and have hard copies available statewide. This will undoubtedly take time, money, and a few other things I might not have at the moment, but with a little hope we’ll get there.

3. You’ve successfully launched a new publication in the middle of a pandemic, when it can be difficult to get people’s attention. How have you managed it?

There’s no doubt we’ve struggled with getting the word out about us. It seems like the whole world is caught up in one frightening current affair after another, and people have little time to devote to reading a small publication — but that isn’t quite right. There has been wonderful support for us between a small group of people, and I think Florida Gael represents a kind of break from the chaos that we all need, with the twist that it’s for a special-interest group: Florida Gael brings together those communities around Florida, which have always been present but scattered, and gathers them into once place to celebrate their culture. I like to think of us as a ‘hearth and home’ for Gaeldom in Florida.

4. Tell us about your background and personal interest in Gaelic culture and Irish history. Are you native Florida, native Irish? And if so, what part of Ireland?

I’m a Floridian! I was raised on the Manatee River, on the eastern border of Bradenton. My mother’s side is Irish on both sides, although there are no paper trails, unfortunately. My interest in Irish history came from some deep-rooted attraction; I have always been interested in Irish culture (and my family’s small customs on St. Patrick’s Day were probably the original inspiration).

When I entered college, I knew I wanted to pursue something in either archaeology or history, and I happened upon a book by historian/antiquitarian P.W. Joyce, The Social History of Ancient Ireland Vol. I. I was immediately hooked. I absolutely knew, at once, that I wanted to become an historian of Irish history. Since then, I earned a B.A. from the Univ. of South Florida in History (European), an M.A. in Early Medieval Irish history from University College Cork in Ireland, and I am currently attending the University of the Highlands and Islands in Scotland (online, although it is not an online university– I had to get special permissions for that one, ha!) for my Ph.D. within the field of Early Medieval Irish history.

5. What do you find the most fun and exciting as publisher of Florida Gael?

The most exciting part about Florida Gael is definitely meeting and interviewing people, and learning about all the different groups and events here in Florida. Sometimes these events are really quite hidden, so it’s exciting when I can happen upon something incredibly interesting and meet equally incredibly interesting people!

6. What can readers do to help support Florida Gael?

Share, share, share. The best thing that readers can do is share out Florida Gael, to anyone that’s ever shown even an inkling of interest. If your grandmother once said, “I sure do love me some corned beef and cabbage,” share it. If your great-uncle (twice removed) mentioned, “you know, we’re descended from that guy in Braveheart,” share it. If you know anyone that’s ever searched for a four-leafed clover, send ’em our link.

Besides sharing it out, reviews on Florida Gael really do help! It not only lets me know that people read and enjoy the content (something which is always wonderful to hear), but it also helps tell Google and Facebook that Florida Gael is something that people are interested in.

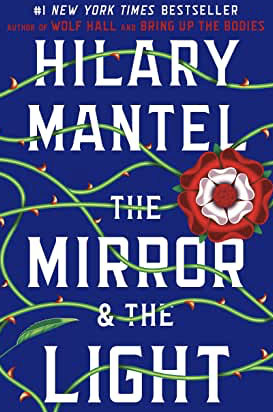

Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex (1485 – 1540) is the protagonist in Mantel’s novel, written entirely from Cromwell’s perspective. This Cromwell (not to be confused with Oliver Cromwell who came along much later) is best remembered as the lawyer who engineered King Henry VIII’s position as head of the Church of England. This allowed the king to annul his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and to then marry Anne Boleyn. From there, Cromwell ascended to higher posts and became chief advisor to the king, who later signed the order for Boleyn’s execution, and would sign the same for Cromwell just a few years after.

Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex (1485 – 1540) is the protagonist in Mantel’s novel, written entirely from Cromwell’s perspective. This Cromwell (not to be confused with Oliver Cromwell who came along much later) is best remembered as the lawyer who engineered King Henry VIII’s position as head of the Church of England. This allowed the king to annul his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and to then marry Anne Boleyn. From there, Cromwell ascended to higher posts and became chief advisor to the king, who later signed the order for Boleyn’s execution, and would sign the same for Cromwell just a few years after.

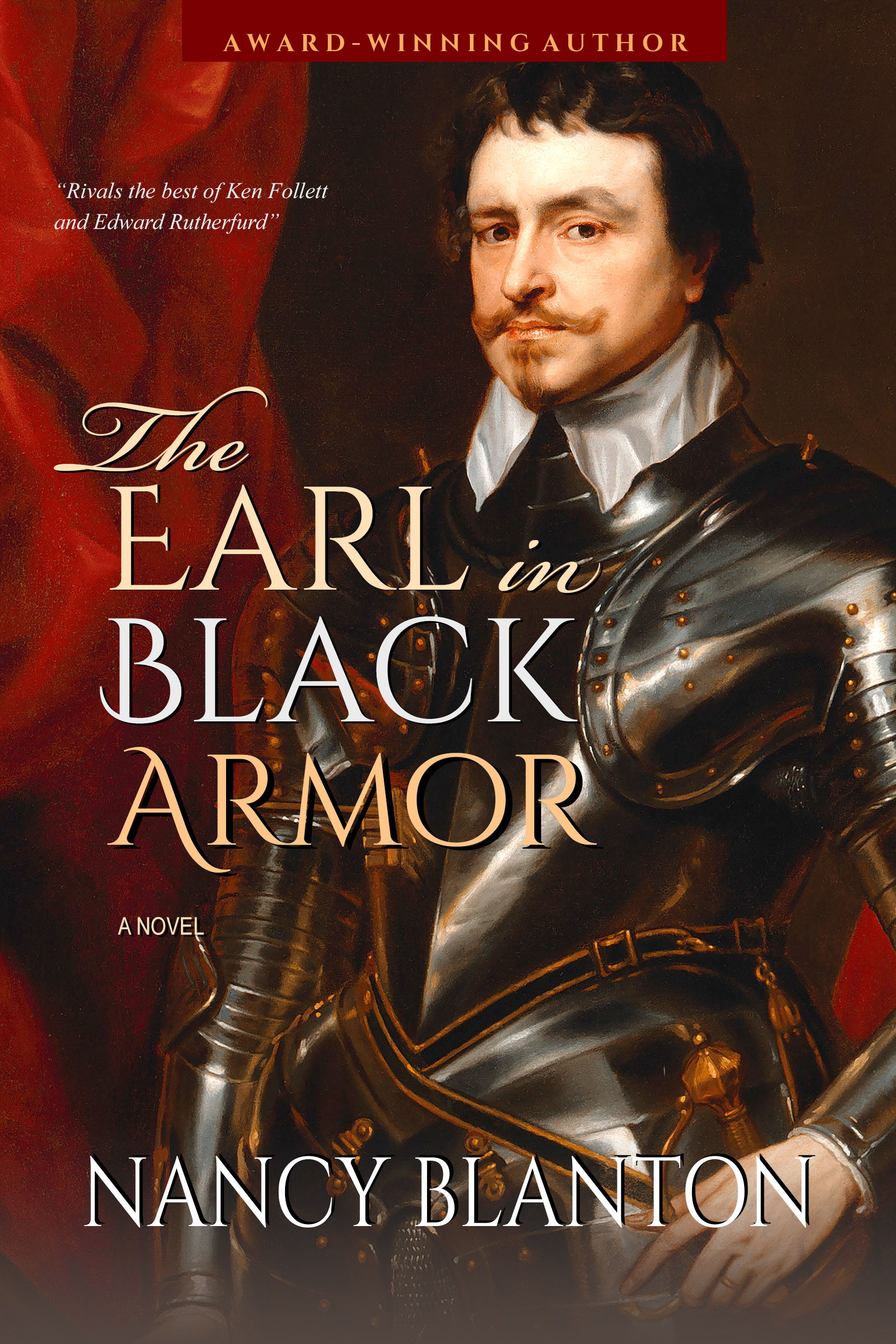

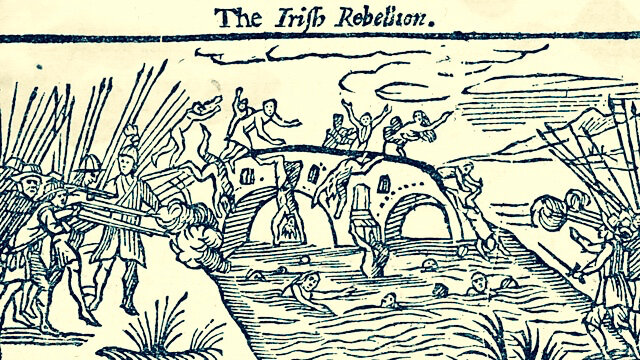

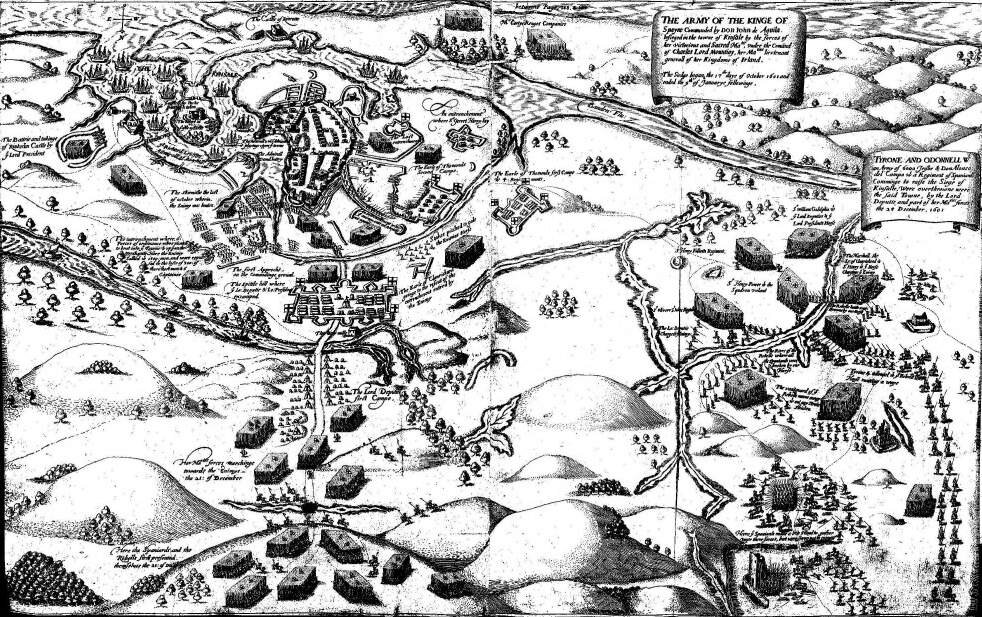

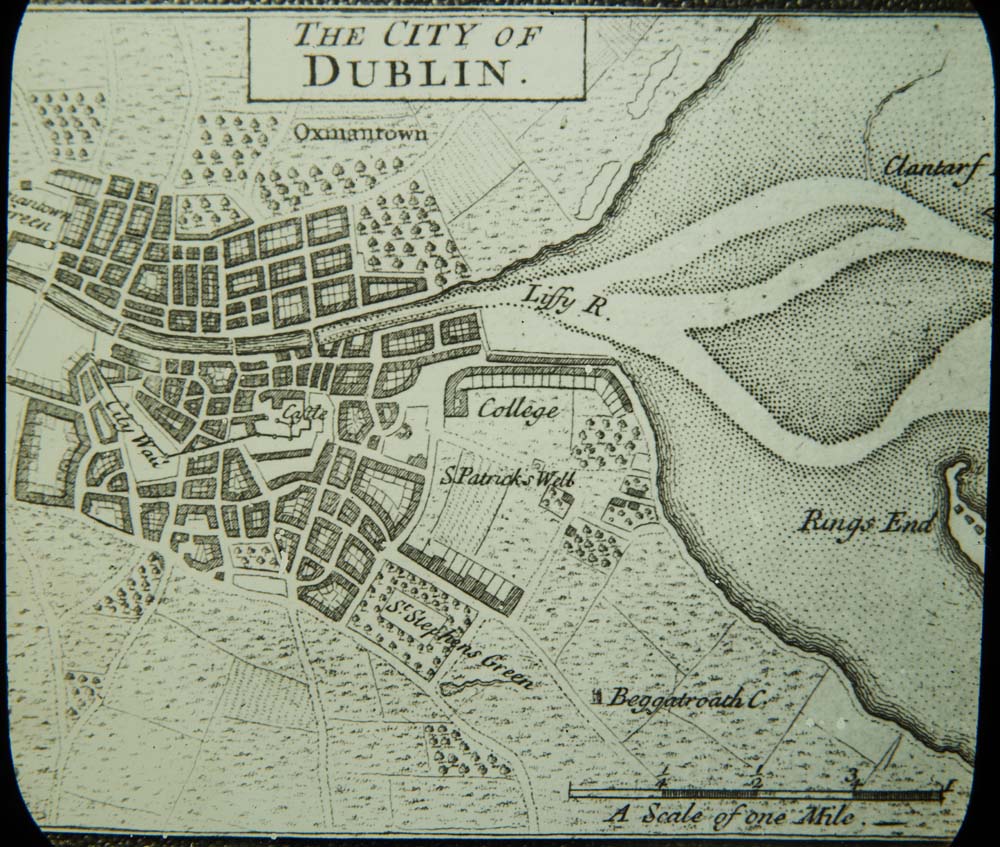

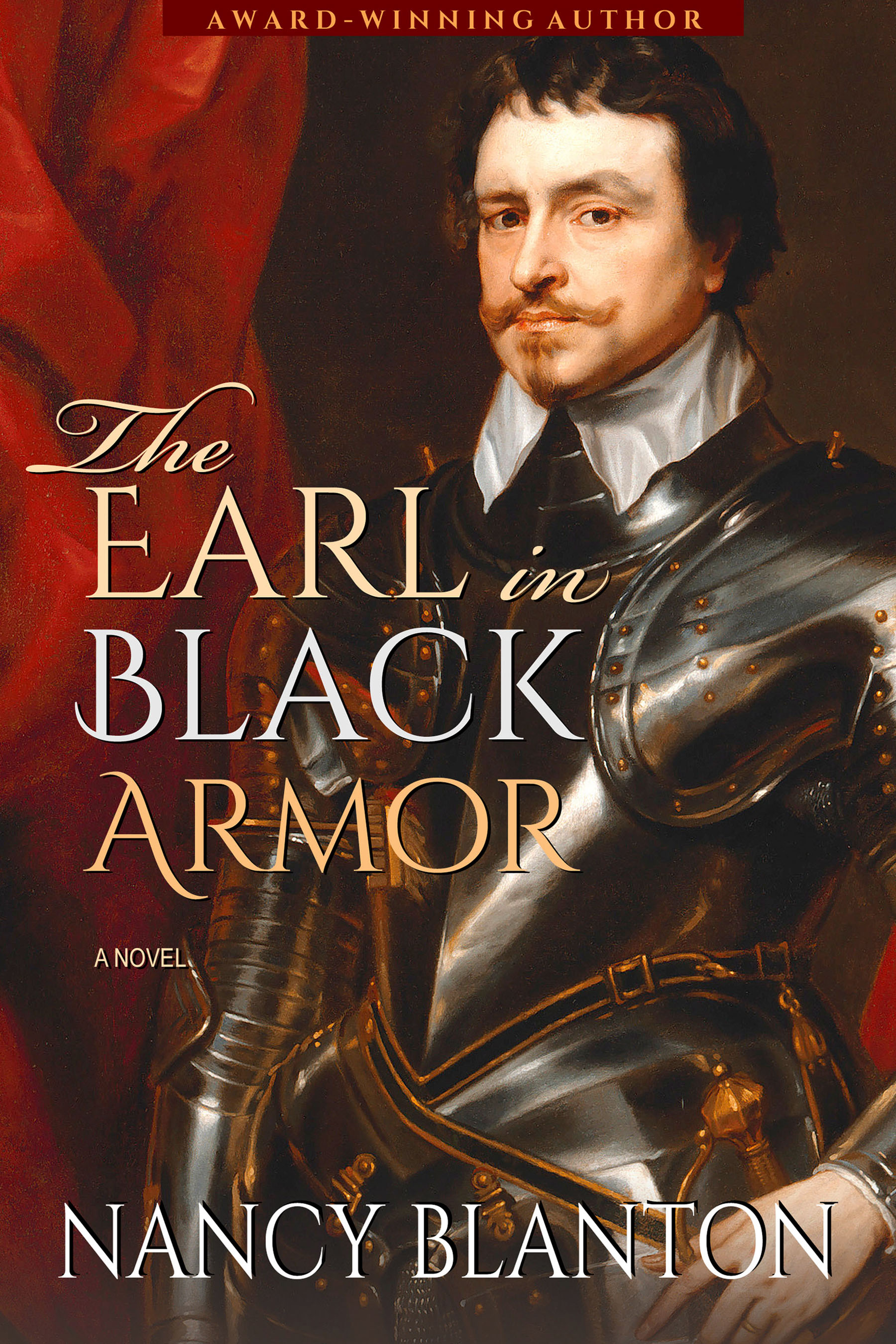

LOYALTY, BETRAYAL, HONOR AND TYRANNY IN THE REIGN OF KING CHARLES IIRELAND, 1635: When the clan leader sends Faolán Burke to Dublin to spy on Thomas Wentworth, the ruthless Lord Deputy of Ireland, the future of his centuries-old clan rests upon his shoulders.

LOYALTY, BETRAYAL, HONOR AND TYRANNY IN THE REIGN OF KING CHARLES IIRELAND, 1635: When the clan leader sends Faolán Burke to Dublin to spy on Thomas Wentworth, the ruthless Lord Deputy of Ireland, the future of his centuries-old clan rests upon his shoulders.